Probability and Deuces in Tennis

I’m always quite pleased to find new an unexpected applications of probability theory. One of my favorite examples is analyzing deuces in tennis. Naievely, one might expect that the probability of winning a game from deuce is the same as the probability of winning a single point. In this post we will see that this expectation is incorrect.

The smallest unit of play in tennis is the point, which consists of a single rally between the two players. The first player to score at least four points while leading their opponent by at least two points wins the game. Tennis uses a slightly nonintuitive system for announcing each player’s score. When a player has no points, their score is “love.” When they have one point, their score is 15. When they have two points, their score is 30. When they have three points, their score is 40. For further details on how tennis is scored, consult Wikipedia.

A game tied at 40-40 is announced as a “deuce.” The player that wins the next point after a deuce is said to have the “advantage.” If the player with the advantage wins the next point, they win the game. If the player with the advantage loses the point, the game is again a deuce, and this process is repeated.

We will analyze the probability that a player wins a game that has resulted in a deuce. Suppose the player in question has probability \(p\) of winning a single point. Two points after a deuce, such a game must either end or return to deuce, so we see that such a game will end an even number of points after the first deuce. The probability that the player wins two points after the first deuce is \[P(\textrm{Win after two points}) = P(\textrm{WW}) = P(\textrm{W}) P(\textrm{W}) = p \cdot p = p^2.\] Here the notation \(\textrm{WW}\) means that the player won both the first and second points. If the player is to win the game four points after the first deuce, there must be a second deuce two points after the first. There are two possible ways to reach the second deuce. The first is that the player wins the first point and loses the second. The second is that the player loses the first point and wins the second. The probability of returning to a deuce after two points is therefore \[P(\textrm{Return to deuce}) = P(\textrm{WL or LW}) = P(\textrm{WL}) + P(\textrm{LW}) = p (1 - p) + (1 - p) p = 2 p (1 - p).\] The probability of of winning the game four points after the first deuce is therefore \[\begin{align} P(\textrm{Win after four points}) & = P(\textrm{Return to deuce}) P(\textrm{Win after two points}) = 2 p (1 - p) \cdot p^2. \end{align}\] If the player wins the game six points after the first deuce, the game must have returned to deuce twice, and therefore \[\begin{align} P(\textrm{Win after six points}) & = P(\textrm{Return to deuce}) P(\textrm{Return to deuce}) P(\textrm{Win after two points}) \\ & = 2 p (1 - p) \cdot 2 p (1 - p) \cdot p^2 = (2 p (1 - p))^2 \cdot p^2. \end{align}\] We can now spot the general pattern, namely that \[P(\textrm{Win after } 2 n \textrm{ points}) = (2 p (1 - p))^{n - 1} \cdot p^2.\] This result is reasonable is reasonable because, to win after \(2 n\) points, we must get spend \(2 (n - 1)\) points returning to deuce \(n - 1\) times and then win the last two points.

We can now evaluate the probability that the player wins after a deuce as \[\begin{align} P(\textrm{Win after deuce}) & = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty P(\textrm{Win after } 2 n \textrm{ points}) \\ & = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty (2 p (1 - p))^{n - 1} \cdot p^2 \\ & = p^2 \sum_{k = 0}^\infty (2 p (1 - p))^k \\ & = \frac{p^2}{1 - 2 p (1 - p)}. \end{align}\] In this third step of this calculation we made the substitution \(k = n - 1\), so that we could directly apply the formula for the sum of a geometric series in the fourth step. We can be sure that this series converges because \(0 < p < 1\) implies that \(0 < 2 p (1 - p ) < 1\).

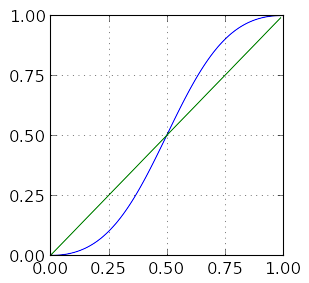

The following plot shows the graph of this function in blue, as well as the graph of the function \(f(p) = p\) in green.

What is most interesting here is that, when \(p > 0.5\), \(P(\textrm{Wins after deuce}) > p\). If a player wins a single point with probability \(p = 0.6\), the probability that they win a game that has reached a deuce is approximately 0.69. If the probability of winning a single point increases to \(p = 0.75\), the probability of winning a game that has reached a deuce is approximately 0.9, an increase of 20%.

We see now that for the better player, the probability of winning a game involving a deuce can be a fair bit larger than the probability of winning a single point.